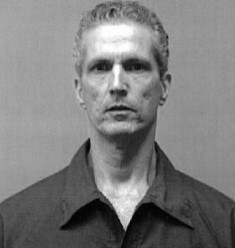

Ralph Armstrong On June 24, 1980, the body of Charise Kamps, a 19-year-old University of Wisconsin student, was found sexually assaulted and murdered in her Gorham Street apartment in Madison, Wisconsin.

The body was discovered by Jane May, who had been partying with Kamps the night before. Kamps was found naked and face down in her blood-soaked bed. She had been strangled, beaten and had injuries to her anus, vagina and throat apparently from insertion of a blunt object.

Among those questioned by police was Ralph Armstrong, May’s fiancé, who was a 27-year-old student at the university and had been released from prison in New Mexico in 1979 on a sodomy conviction and four rape convictions.

Armstrong told police that he, May, Kamps and others had been at Namio’s restaurant the night before, then went to May’s apartment where they drank and did drugs, including cocaine. He said that he had been at Kamps’ apartment earlier, but returned to spend the night with May. He gave hair samples and agreed to allow a crime lab analyst to take scrapings underneath his fingernais and toenails. When a presumptive test identified blood under all of his fingernails and some of his toes, he was taken into custody.

Police also questioned Armstrong’s brother, Steven, who was visiting him at the time, but he was discounted as a suspect and released.

On July 3, Ralph Armstrong was charged with the murder of Kamps after a witness, Riccie Orebia, identified him. Orebia lived across the street from Kamps’s apartment. She told police that at about 12:30 p.m., she was on her front porch when she saw a white car with a black top pass on West Gorham and described the driver as having dark, shoulder-length hair. Orebia saw the car pass a second time and park out of view across the street.

About five or ten minutes later, Orebia saw a person walk from the direction of the parking lot, cross the street, and enter Kamps’s apartment building. Orebia described the person as lean and very muscular. About five to ten minutes after that, the same man left the building and headed back from where he came. Orebia said that another five minutes passed and the same man crossed the street, entered the building a second time, and then, after staying inside another five minutes, left again this time without wearing a shirt. Orebia said that five more minutes passed, and the same person ran across the street to the building a third time, stayed for about 20 minutes, and then left running very fast, "shining" as if he were sweating. Orebia then observed the black-over-white car speeding away from the parking lot.

Several days after the murder and prior to any police identification procedure, Orebia underwent hypnosis. Dr. Roger A. McKinley performed the hypnosis and Madison Police Detective Robert Lombardo was present.

In the early morning hours of July 1, 1980, after Orebia had undergone hypnosis, police arranged a line-up procedure at Kamps’s apartment building. But Armstrong refused to cooperate upon instruction from his attorney, Dennis Burke. The police then returned Armstrong to jail and tried again in the early morning hours of July 3, 1980.

At about 4:00 a.m. on July 3, police told Armstrong to put on a shirt, a pair of jeans and a pair of cowboy boots to match the other line-up participants, but Armstrong refused. They took him to West Gorham with four other line-up participants and each were walked up to the porch of Kamps's apartment and then back in the opposite direction. Armstrong was the second person to go and he went limp as soon as he and the two officers accompanying him came into view of the observers standing on Orebia’s porch. Two officers dragged him up to the porch of Kamps's apartment and back again. One officer testified that Armstrong lost his shoes along the way and made the statement, "better a little pain now than life imprisonment later." The police took the three remaining participants along the same route.

By this time, the daylight had broken and the five line-up participants were then each held by two police officers in front of a police van and Orebia was brought down to the parking lot to observe. From 25 feet away, Orebia picked Armstrong.

Months later, on November 5, 1980, Orebia gave a statement under oath at Armstrong's attorney's office in the presence of a court reporter and an investigator, Charles Lulling, in which Orebia directly contradicted her identification of Armstrong to the police. In that statement, Orebia said that Armstrong could not have been the person she saw running in and out of Kamps’s apartment.

Orebia gave a second statement to the defense on November 10, 1980, indicating that she had read through the statement she had given five days prior and that it was true and correct.

In March 1981, Armstrong went to trial in Dane County Circuit Court. The hypnotist, Dr. McKinley, testified that prior to hypnosis, Orebia described the man she saw as having shoulder-length hair and a muscular build and that he was running and sweating. McKinley testified that during the hypnotic session, Orebia described particular features of the suspect's face, including that the suspect had a long nose and bushy eyebrows.

McKinley admitted that if Orebia would not have been able to make out the detail of Armstrong's face because of lighting conditions, then any description she gave of Armstrong's nose, eyebrows, and other features would have to be "confabulation."

Photographs of Armstrong and the vehicle were passed between Lombardo and McKinley during session in front of Orebia. McKinley testified that in his presence Orebia was never shown photographs of Armstrong.

However, Lombardo testified that Orebia saw photographs of Armstrong's vehicle when he handed them to McKinley during the session and that Orebia had also seen photos of the car prior to hypnosis.

McKinley defended his hypnosis procedure with Orebia as non-suggestive.

Orebia testified and recanted her recantation. She said that she was positive that Armstrong was the person she saw enter and leave Kamps's apartment building three times that night. Orebia testified that upon seeing Armstrong's head come into view during the first portion of the line-up, she gasped and mentioned to police officers standing with him that Armstrong was the person she saw leaving the murder scene.

Orebia also stated that she realized that two line-up participants, including the first participant, were wearing shoulder-length wigs and mentioned that observation to the officers standing nearby. Orebia testified that the police told her that they had a man in custody who would be in the line-up, however, the police also instructed Orebia not to pick anyone unless she was sure. Orebia admitted she told Armstrong’s attorney that she thought the line-up was fixed.

Orebia testified that the statements she gave on 5 and 10, 1980, were purposely untruthful, told as deliberate lies to undermine her credibility as a witness and to hopefully result in her withdrawal as a witness.

Armstrong presented Dr. John Fournier, an ophthalmologist, to refute the ability of Orebia to make certain observations. Fournier measured the distances and lighting conditions from Orebia's vantage point on her porch to the route of the person she observed. Fournier testified that night vision acuity is about 1/10 that of daytime vision, and that given the conditions under which Orebia made her observations—a distance of 100 to 134 feet and under low illumination from the street lamps with glare in the foreground—it was not physically possible for a person in Orebia's position to make out facial features—as she said during the hypnosis session.

Armstrong also presented the testimony of Dr. John F. Kihlstrom, a psychology professor who testified to the effects of hypnosis on memory. Kihlstrom stated that hypnosis could be used to access memories that are not ordinarily memorable in the wakened state, but the hypnotist also runs an equal risk of confabulation. Kihlstrom stated that precautions to limit the introduction of inadvertent suggestion include keeping the hypnotist blind to the facts of the case, and to conduct the session out of the presence of an investigator who could suggest particular views.

Kihlstrom presented excerpts from the videotaped session between McKinley and Orebia. Kihlstrom noted that Lombardo was in the room during the session, and that Orebia initially described the suspect as being 5 feet, 3 inches to 5 feet 5 inches tall, but McKinley suggestively inquired about a height of 6 feet tall until Orebia agreed with that height. Armstrong was 6 feet, 2 inches tall.

Armstrong was convicted by a jury on March 24, 1981 and sentenced to life plus 16 years in prison.

His appeals were denied.

After DNA testing became available as a means of proving innocence, Armstrong began petitioning for testing of the evidence in the case.

In 2001, a judge refused to grant him a new trial despite DNA evidence on two head hairs found on the belt of a bathrobe lying on Kamps’ body. At Armstrong’s trial, a crime lab analyst said one of the hairs was similar with Armstrong’s hair and the other was consistent with Armstrong’s hair.

The DNA tests showed neither hair was Armstrong’s. However, a judge ruled that the evidence would not have changed the verdict.

But in July 2005, the Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed Armstrong’s conviction, saying that the DNA evidence was sufficient to support a motion for a new trial.

Before Armstrong could be retried, however, defense lawyers sought to dismiss the case entirely.

In April 2007, Armstrong’s lawyers contended that the prosecutor in the case, Dane County Assistant District Attorney John Norsetter had violated a court order by sending evidence in the case—a semen stain on the bathrobe—for DNA testing. As a result, the evidence was consumed and was unavailable for testing by the defense.

Moreover, two new witnesses surfaced—both of whom said that after Armstrong was convicted, his brother, Stephen, had confessed to them that he had committed the crime. By then, Stephen Armstrong was dead.

Both witnesses said they had reached out to Norsetter to tell him of Stephen Armstrong’s confession, but he refused to believe them. More significantly, he never told Ralph Armstrong’s defense attorneys.

On July 30, 2009, a judge dismissed the charges against Armstrong, based on his findings that Norsetter had violated a court order and essentially destroyed potentially exculpatory biological evidence, and that Norsetter had failed to inform the defense of Stephen Armstrong’s confession.

On August 19, 2009, the state said it would not appeal the decision and the charges were dismissed. Armstrong, who was wanted for parole violations in New Mexico, was transferred to prison there. His parole was revoked in September 2010 and he was ordered to resume serving the 30- to 150-year sentence he had received for the sex crime convictions in 1972. In 2013, he was released on parole again.

He brought a civil rights suit against the prosecutor on his case, John Norsetter, and two crime lab workers, Karen Daily and Dan Campbell. The defendants filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit on immunity grounds, but a U.S. District Judge denied the motion. In May 2015, the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals upheld that ruling.

The appeals court held: "Armstrong alleges a shocking course of prosecutorial misconduct. According to the complaint, the prosecutor quickly fixated on Armstrong as the murderer and sought to build a case against him by any means necessary.

"Those means included destroying potentially exculpatory evidence from the crime scene, arranging for the highly suggestive hypnosis of an eyewitness, contriving suggestive show - ups for identification, and concealing a later confession from the true killer that was relayed by a person with no apparent motive to fabricate the report," the appeals court said.

"Finally, the prosecutor enlisted state lab technicians to perform an inconclusive DNA test that consumed the last of a sample that could have proven Armstrong’s innocence and pointed to the true killer. If these allegations are true — and some are based on the state court’s factual findings — the prosecution of Armstrong was a single-minded pursuit of an innocent man that let the real killer to go free," the appeals court ruled.

The state of Wisconsin, Dane County and the city of Madison settled the lawsuit for $1,750,000 in February 2017. At that time, Armstrong was back in prison after violating his parole.

– Maurice Possley

|